- Posts: 1001

- Thank you received: 1158

Little stories

- Sqdn. Ldr. Ted Striker

-

- Offline

Less

More

5 years 1 week ago #49

by Sqdn. Ldr. Ted Striker

Replied by Sqdn. Ldr. Ted Striker on topic Little stories

Quite interesting to read, I just wonder what is a “Nazi soldier”? The term is used gladly and often but uncritically. Ok, nobody questions it.

The following user(s) said Thank You: Damni, p.jakub88

Please Log in or Create an account to join the conversation.

- Maki

-

- Offline

Less

More

- Posts: 1273

- Thank you received: 1800

5 years 4 days ago #50

by Maki

Replied by Maki on topic Little stories

Just one Canadian tank made it to VE Day

The 14,000 Canadians and 200 tanks that landed at Juno Beach on June 6, 1944 fought bitterly to breach Fortress Europe and begin the long march to Berlin. Almost a year later Canada and the rest of the Allied powers celebrated the fall of Germany.

Crewmembers and officers who served on the Bomb pose with it on Jun. 8, 1945 in the Netherlands.

Only one Canadian tank from those 200 fought every day of the invasion across Western Europe. “Bomb,” a Sherman, travelled 4,000 miles and fired 6,000 rounds while fighting the Germans. From Juno Beach, Bomb was sent northeast to the Netherlands through Belgium before cutting east towards Berlin.

A tank from the Bomb’s regiment, possibly the Bomb itself, hunts snipers in Falaise, France in 1944.

Soon after Bomb crossed into Germany near Emden, Bomb was sent to Kleve on the German side of the border with the Netherlands. In the early morning of Feb. 26, 1945 Bomb escorted a column of infantry in armored vehicles forward. German artillery opened up and pinned the column down in thick mud.

The Germans put up a smoke screen and continued their attack. But the Bomb led a counterattack that relieved the pressure. Surrounded by German anti-tank teams and under heavy mortar, artillery, and machine gun fire, Bomb and another Canadian tank held their ground for 20 minutes until infantry was able to reinforce them, stopping the Germans from destroying the Canadian column.

Neill was later awarded the Military Cross for the battle.

As the war wound to a close, the Bomb found itself in continuously heavy combat. On the last day of the European war, the Bomb was under the command of Lt. Ernest Mingo. He and his men faced off against a German officer who kept sending soldiers to try and Allied Forces.

“The land between us was covered with dead German soldiers,” he said, according to a Sunday Daily News article. “He must have known the war was over, but he just kept sending them out, I guess trying to kill Canadians.”

Despite being the only Canadian tank to serve every day of the war in Europe, the Bomb was nearly melted down as scrap in Belgium after the war. It was rescued and went on display in 1947. In 2011 the tank underwent restoration. It is currently at the Sherbrooke Hussars Armoury in Sherbrooke, Quebec.

The 14,000 Canadians and 200 tanks that landed at Juno Beach on June 6, 1944 fought bitterly to breach Fortress Europe and begin the long march to Berlin. Almost a year later Canada and the rest of the Allied powers celebrated the fall of Germany.

Crewmembers and officers who served on the Bomb pose with it on Jun. 8, 1945 in the Netherlands.

Only one Canadian tank from those 200 fought every day of the invasion across Western Europe. “Bomb,” a Sherman, travelled 4,000 miles and fired 6,000 rounds while fighting the Germans. From Juno Beach, Bomb was sent northeast to the Netherlands through Belgium before cutting east towards Berlin.

A tank from the Bomb’s regiment, possibly the Bomb itself, hunts snipers in Falaise, France in 1944.

Soon after Bomb crossed into Germany near Emden, Bomb was sent to Kleve on the German side of the border with the Netherlands. In the early morning of Feb. 26, 1945 Bomb escorted a column of infantry in armored vehicles forward. German artillery opened up and pinned the column down in thick mud.

The Germans put up a smoke screen and continued their attack. But the Bomb led a counterattack that relieved the pressure. Surrounded by German anti-tank teams and under heavy mortar, artillery, and machine gun fire, Bomb and another Canadian tank held their ground for 20 minutes until infantry was able to reinforce them, stopping the Germans from destroying the Canadian column.

Neill was later awarded the Military Cross for the battle.

As the war wound to a close, the Bomb found itself in continuously heavy combat. On the last day of the European war, the Bomb was under the command of Lt. Ernest Mingo. He and his men faced off against a German officer who kept sending soldiers to try and Allied Forces.

“The land between us was covered with dead German soldiers,” he said, according to a Sunday Daily News article. “He must have known the war was over, but he just kept sending them out, I guess trying to kill Canadians.”

Despite being the only Canadian tank to serve every day of the war in Europe, the Bomb was nearly melted down as scrap in Belgium after the war. It was rescued and went on display in 1947. In 2011 the tank underwent restoration. It is currently at the Sherbrooke Hussars Armoury in Sherbrooke, Quebec.

The following user(s) said Thank You: snowman, Damni, p.jakub88

Please Log in or Create an account to join the conversation.

- Maki

-

- Offline

Less

More

- Posts: 1273

- Thank you received: 1800

4 years 11 months ago #51

by Maki

Replied by Maki on topic Little stories

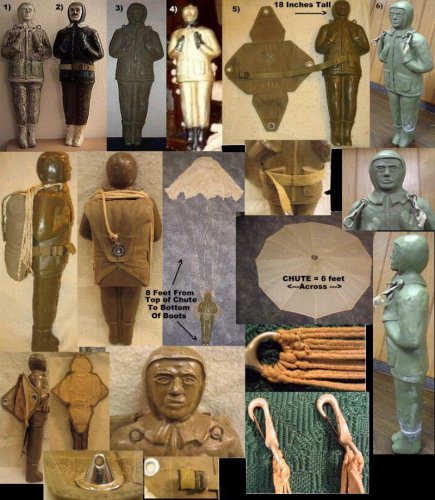

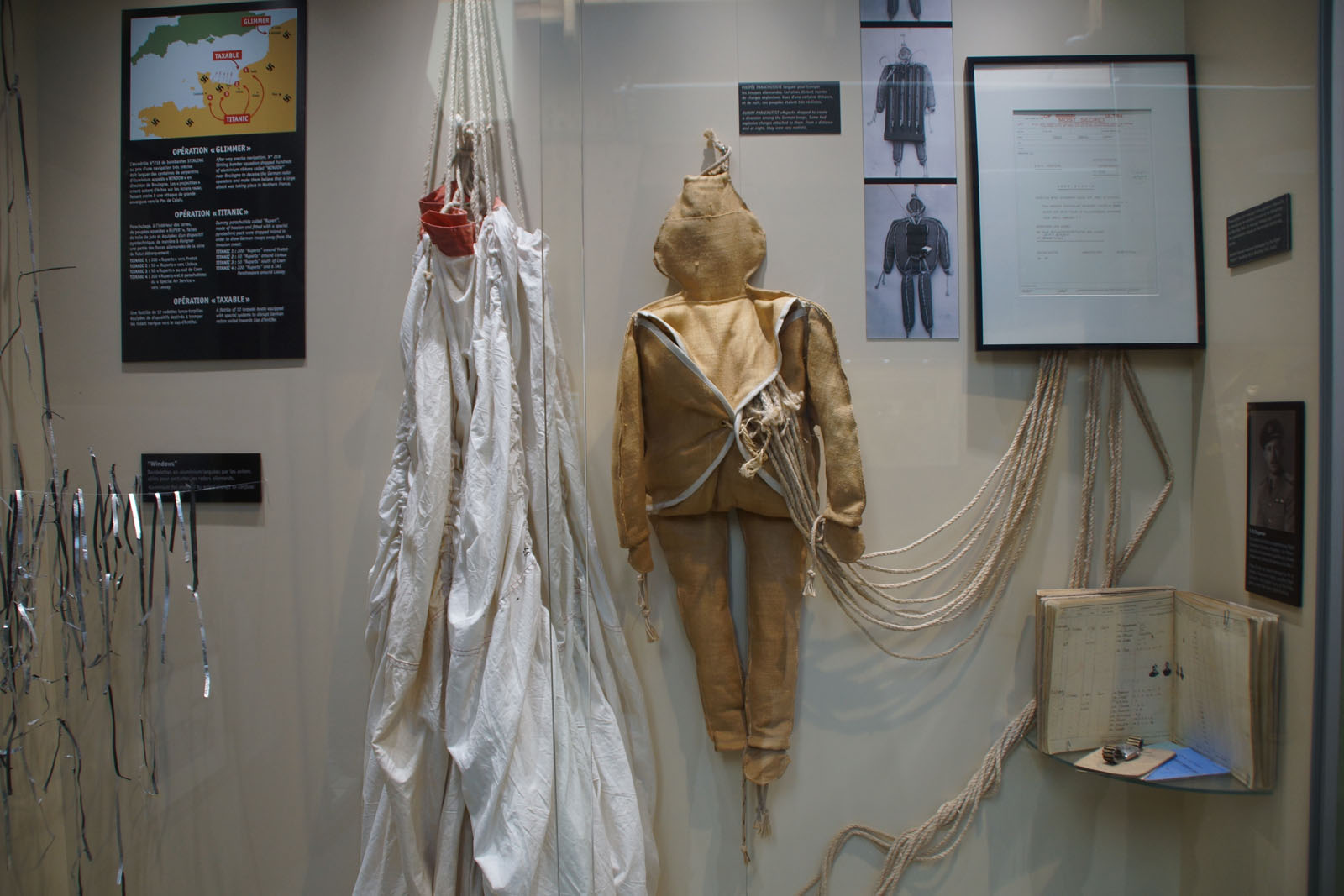

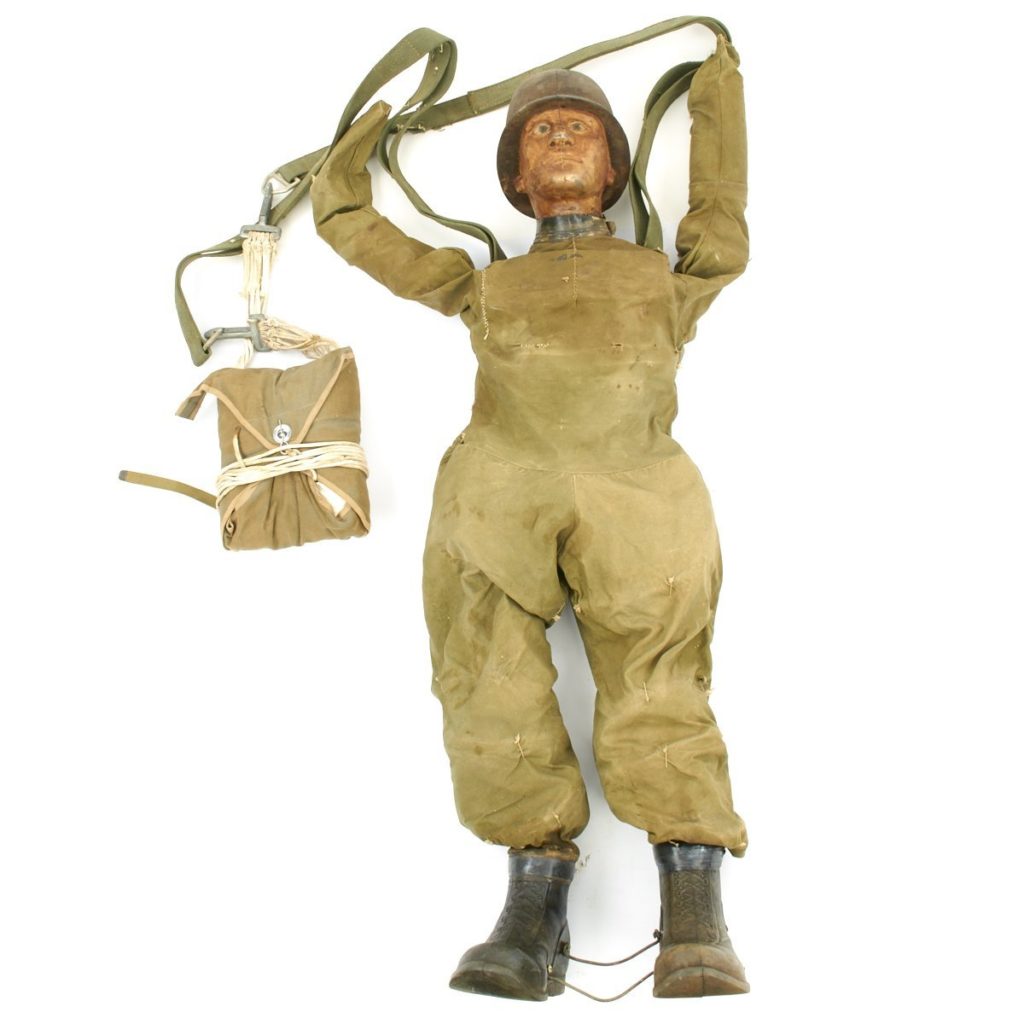

The paradummy that distracted the Germans on D-Day

The Chinese military strategist and philosopher Sun Tzu said, “All warfare is based on deception.” Like a trick play in football, it’s best to deceive your enemy in order to safeguard your true intentions. One of the greatest modern military examples of this principle is the allied landing at Normandy on D-Day during WWII.

Operation Overlord, the allied invasion of Nazi-occupied mainland Europe, involved the largest invasion force ever assembled. The prelude to the operation involved numerous deception campaigns including a fake army staged at Dover and the leaking of false plans to convince the Germans that the invasion would happen at Calais. However, once the invasion started at Normandy, there was one more trick that the allies had up their sleeves.

A paradummy featured in The Longest Day (20th Century Fox)

On the evening of June 5th into June 6th, 1944, thousands of allied paratroopers dropped over the skies of Normandy. They were tasked with eliminating German positions, seizing key roads and bridges, and generally causing mayhem and confusion behind German lines in support of the beach landings. However, they weren’t the only ones riding the silk elevator on D-Day. To further confuse the Germans, hundreds of dummy paratroopers were also dropped over Normandy and Calais.

Called “Ruperts” by the British and “Oscars” by the Americans, these paradummies were part of Operation Titanic. Helping to sell the illusion that the invasion at Normandy was a feint while the main invasion was at Calais, the paradummies were dropped east of the main landing zones. The dummies came in different variants and proved to be very effective at confusing the Germans during the first few hours of the invasion.

Some Ruperts were only about the size of a child’s doll and worked best when viewed at a distance. Others were full-sized and equipped with uniforms, helmets, and boots. They were also made with varying degrees of detail from featureless forms to detailed faces and even painted eyes. To simulate a real invasion force, some of the dummies were equipped with speakers that played sounds of gunfire and mortars while others were rigged to explode upon landing. The Ruperts were made of burlap or rubber and were convincing enough to draw away part of the SS Panzer reinforcement sent to repel the British at Caen.

In the 1962 film The Longest Day

While the silk parachutes used by the allies were sought after by civilians due to the scarcity of the material from wartime rationing, the Ruperts were less so. Though burlap was a useful material, the risk of an unexploded charge going off late convinced most civilians to leave the paradummies alone. Because of this, few examples of the dummy troopers survive in museums today.

The Chinese military strategist and philosopher Sun Tzu said, “All warfare is based on deception.” Like a trick play in football, it’s best to deceive your enemy in order to safeguard your true intentions. One of the greatest modern military examples of this principle is the allied landing at Normandy on D-Day during WWII.

Operation Overlord, the allied invasion of Nazi-occupied mainland Europe, involved the largest invasion force ever assembled. The prelude to the operation involved numerous deception campaigns including a fake army staged at Dover and the leaking of false plans to convince the Germans that the invasion would happen at Calais. However, once the invasion started at Normandy, there was one more trick that the allies had up their sleeves.

A paradummy featured in The Longest Day (20th Century Fox)

On the evening of June 5th into June 6th, 1944, thousands of allied paratroopers dropped over the skies of Normandy. They were tasked with eliminating German positions, seizing key roads and bridges, and generally causing mayhem and confusion behind German lines in support of the beach landings. However, they weren’t the only ones riding the silk elevator on D-Day. To further confuse the Germans, hundreds of dummy paratroopers were also dropped over Normandy and Calais.

Called “Ruperts” by the British and “Oscars” by the Americans, these paradummies were part of Operation Titanic. Helping to sell the illusion that the invasion at Normandy was a feint while the main invasion was at Calais, the paradummies were dropped east of the main landing zones. The dummies came in different variants and proved to be very effective at confusing the Germans during the first few hours of the invasion.

Some Ruperts were only about the size of a child’s doll and worked best when viewed at a distance. Others were full-sized and equipped with uniforms, helmets, and boots. They were also made with varying degrees of detail from featureless forms to detailed faces and even painted eyes. To simulate a real invasion force, some of the dummies were equipped with speakers that played sounds of gunfire and mortars while others were rigged to explode upon landing. The Ruperts were made of burlap or rubber and were convincing enough to draw away part of the SS Panzer reinforcement sent to repel the British at Caen.

In the 1962 film The Longest Day

While the silk parachutes used by the allies were sought after by civilians due to the scarcity of the material from wartime rationing, the Ruperts were less so. Though burlap was a useful material, the risk of an unexploded charge going off late convinced most civilians to leave the paradummies alone. Because of this, few examples of the dummy troopers survive in museums today.

The following user(s) said Thank You: snowman, Odysseus

Please Log in or Create an account to join the conversation.

- snowman

-

- Offline

- Your most dear friend.

4 years 11 months ago #52

by snowman

The following user(s) said Thank You: Maki

Please Log in or Create an account to join the conversation.

- Maki

-

- Offline

Less

More

- Posts: 1273

- Thank you received: 1800

4 years 10 months ago - 4 years 10 months ago #53

by Maki

The German Kriegsmarine was once one of the most feared military forces on Earth, particularly the U-boat fleet. While the German surface fleet was smaller and weaker than the navies of its opponents, the “wolf packs” patrolled beneath the waves, shattering Allied convoys and robbing Germany’s enemies of needed men and materiel.

A German sailor works on U-boat communications.

But the U-boats didn’t do this on their own. One of the most successful code-breaking efforts in the war was that of the Beobachtung Dienst, the Observation Service, of German naval intelligence.The German service focused its efforts on decoding the signals used by the major Allied navies — Great Britain, the U.S., and the Soviet Union — as well as traffic analysis and radio direction finding. With these three efforts combined, they could often read Allied communications. When they couldn’t, the traffic analysis and radio direction finding made them great guessers at where convoys would be.B-Dienst peaked in World War II at 5,000 personnel focused on cracking the increasingly complex codes made possible by mechanical computers . The head of the English-language section, the one focused on the U.S. and U.K., was Wilhelm Tranow, a former radioman who earned a reputation in World War I for figuring out British codes and passing them up the chain.

.

A lean but effective infrastructure grew around Tranow and his team. At their best, the team was able to intercept communications between Allied elements and pass actionable intelligence to U-boat captains within a few hours . Their efforts allowed Germany to read up to 80 percent of British communications that were intercepted. For most of the war, they were reading at least a third of all intercepted communications.Allied merchant marine and navy personnel were rightly afraid of U-boat attacks, but they seem to have underestimated how large a role the B-Dienst and other German intelligence services played. This led them to make errors that made the already-capable B-Dienst even more effective.First, Allied communications contained more data than was strictly necessary. The chatter between ships as they headed out could often give German interceptors the number of ships in a convoy, its assembly point, its anticipated speed and heading, where it would meet up with stragglers, and how many escorts it had.

A destroyer, the USS Fiske, sinks after being struck by a German U-boat torpedo.

This allowed B-Dienst to identify the most vulnerable convoys and guess where and when the convoy would move into wolf-pack territory.Nearly as damaging, the British would sometimes send out the same communications using different codes. When the British were using some codes the Germans didn’t know, these repeated messages end up becoming a Rosetta Stone-like windfall for the intercepting Germans. They could identify the patterns in the two codes and use breakthroughs in one to translate the other, then use the translations to break that code entirely.When the Allies weren’t repeating entire messages, they were sending messages created with templates . These templates, which repeated the same header and closer on each transmission, gave the Germans a consistent starting point. From there, they could suss out how the code worked.

All of this was compounded by a tendency of the British in particular and the Allied forces in general to be slow in changing codes.So, it took the British months after they learned that the Germans had broken the Naval Code and Naval Cypher to change their codes. The change was made in August 1940 and was applied to communications between the U.S. and Royal navies in June 1941.

But with the other missteps allowing the B-Dienst to get glimmers of how the code worked, the code was basically useless by the end of 1942.

This had real and devastating effects for Allied naval forces who were attempting to pass through U-boat territory as secretly as possible. 875 Allied ships were lost in 1941 and 1,664 sank in 1942, nearly choking the British Isles below survivable levels.But, despite the B-Dienst success, the Battle of the Atlantic started to shift in favor of the Allies in 1942, mostly thanks to increases in naval forces and advanced technology like radar and sonar becoming more prevalent. Destroyers were more widely deployed and could more quickly pinpoint and attack the U-boats.

New anti-submarine planes, weapons like the “Hedgehog,” and better tactics led to the “Black May” of 1943 when the Allies sank approximately one quarter of all U-boats . The German ships were largely withdrawn from the Atlantic, and convoys could finally move with some degree of security.

Replied by Maki on topic Little stories

Those Germans cracked codes like wishbones

The German Kriegsmarine was once one of the most feared military forces on Earth, particularly the U-boat fleet. While the German surface fleet was smaller and weaker than the navies of its opponents, the “wolf packs” patrolled beneath the waves, shattering Allied convoys and robbing Germany’s enemies of needed men and materiel.

A German sailor works on U-boat communications.

But the U-boats didn’t do this on their own. One of the most successful code-breaking efforts in the war was that of the Beobachtung Dienst, the Observation Service, of German naval intelligence.The German service focused its efforts on decoding the signals used by the major Allied navies — Great Britain, the U.S., and the Soviet Union — as well as traffic analysis and radio direction finding. With these three efforts combined, they could often read Allied communications. When they couldn’t, the traffic analysis and radio direction finding made them great guessers at where convoys would be.B-Dienst peaked in World War II at 5,000 personnel focused on cracking the increasingly complex codes made possible by mechanical computers . The head of the English-language section, the one focused on the U.S. and U.K., was Wilhelm Tranow, a former radioman who earned a reputation in World War I for figuring out British codes and passing them up the chain.

.

A lean but effective infrastructure grew around Tranow and his team. At their best, the team was able to intercept communications between Allied elements and pass actionable intelligence to U-boat captains within a few hours . Their efforts allowed Germany to read up to 80 percent of British communications that were intercepted. For most of the war, they were reading at least a third of all intercepted communications.Allied merchant marine and navy personnel were rightly afraid of U-boat attacks, but they seem to have underestimated how large a role the B-Dienst and other German intelligence services played. This led them to make errors that made the already-capable B-Dienst even more effective.First, Allied communications contained more data than was strictly necessary. The chatter between ships as they headed out could often give German interceptors the number of ships in a convoy, its assembly point, its anticipated speed and heading, where it would meet up with stragglers, and how many escorts it had.

A destroyer, the USS Fiske, sinks after being struck by a German U-boat torpedo.

This allowed B-Dienst to identify the most vulnerable convoys and guess where and when the convoy would move into wolf-pack territory.Nearly as damaging, the British would sometimes send out the same communications using different codes. When the British were using some codes the Germans didn’t know, these repeated messages end up becoming a Rosetta Stone-like windfall for the intercepting Germans. They could identify the patterns in the two codes and use breakthroughs in one to translate the other, then use the translations to break that code entirely.When the Allies weren’t repeating entire messages, they were sending messages created with templates . These templates, which repeated the same header and closer on each transmission, gave the Germans a consistent starting point. From there, they could suss out how the code worked.

All of this was compounded by a tendency of the British in particular and the Allied forces in general to be slow in changing codes.So, it took the British months after they learned that the Germans had broken the Naval Code and Naval Cypher to change their codes. The change was made in August 1940 and was applied to communications between the U.S. and Royal navies in June 1941.

But with the other missteps allowing the B-Dienst to get glimmers of how the code worked, the code was basically useless by the end of 1942.

This had real and devastating effects for Allied naval forces who were attempting to pass through U-boat territory as secretly as possible. 875 Allied ships were lost in 1941 and 1,664 sank in 1942, nearly choking the British Isles below survivable levels.But, despite the B-Dienst success, the Battle of the Atlantic started to shift in favor of the Allies in 1942, mostly thanks to increases in naval forces and advanced technology like radar and sonar becoming more prevalent. Destroyers were more widely deployed and could more quickly pinpoint and attack the U-boats.

New anti-submarine planes, weapons like the “Hedgehog,” and better tactics led to the “Black May” of 1943 when the Allies sank approximately one quarter of all U-boats . The German ships were largely withdrawn from the Atlantic, and convoys could finally move with some degree of security.

Last edit: 4 years 10 months ago by snowman. Reason: Helped again with text formatting :)

The following user(s) said Thank You: snowman, Stompinidus

Please Log in or Create an account to join the conversation.

- Maki

-

- Offline

Less

More

- Posts: 1273

- Thank you received: 1800

4 years 10 months ago - 4 years 10 months ago #54

by Maki

A s members of England’s First Aid Nursing Yeomanry, or FANYs, during World War II, Odette Sansom, Violette Szabó, and Noor Inayat Khan might have worked in hospitals, driven ambulances, sent coded radio signals, fixed trucks, or even, as one FANY did during the war, taught the future Queen Elizabeth to drive. But when British Prime Minister Winston Churchill instructed the nation’s clandestine spy agency, the Special Operations Executive (SOE), to “set Europe ablaze,” the three FANYs merged their nursing roles with espionage.

The SOE, which carried out audacious sabotage plots across Europe, recruited 2,000 FANY members to the secret service. But only 39 went into the field to conduct commando operations, including Sansom, Szabó, and Khan.Each brought her unique upbringing to her missions. Sansom (pictured above) and Szabó were both born in France; Sansom to a French man killed in World War I, whereas Szabó’s father had been an English soldier. Khan was a Muslim from India descended from a sultan. But their French fluency and familiarity with military skills like marksmanship caught the eye of England’s spy masters. The commandos working for SOE in North Africa, the Far East, and particularly across Europe were the No. 1 targets of the Gestapo and the Abwehr, German military intelligence. “From now on, all men operating against German troops in so-called Commando raids in Europe or in Africa, are to be annihilated to the last man,” read Adolf Hitler’s secret Commando Order (Kommandobefehl) issued on Oct. 18, 1942. If members of the SOE were discovered, man or woman, they’d be hunted, tortured, and executed.

Noor Inayat Khan was a Muslim princess who volunteered for the British Special Operations Executive (SOE) during World War II. She became one of the first women awarded the George Cross, the United Kingdom’s highest civilian honor. It was accepted posthumously on her behalf.

Sansom, Szabó, and Khan had to be discreet and keep their identities secret. They carried false papers with fake names, home addresses, and occupations. Virginia Hall, famously known as “The Limping Lady,” who served with the SOE early in the war, used a cover as a French American stringer for the New York Post writing under the public persona of Brigitte LeContre. The FANYs received training in weapons handling, fieldcraft, and sabotage, and assumed their own disguises. Sansom took the code name Lise as a courier for the Spindle spy ring, or “circuit” under the SOE’s F Section (France). Circuits were generally composed of three officers: a circuit leader, a courier, and a radio operator. A wife and mother of three children, Sansom transported messages and money to associates in the French Resistance.

After seven months of clandestine fieldwork, she was captured by the german officer Hugo Bleicher , a notorious spy catcher who personally arrested more than 100 agents and officers. Sansom was interrogated for hours at Fresnes Prison in Paris, subjected to techniques including the removal of her toenails. When she wouldn’t confess, the Nazis sent her to Ravensbrück, the most feared concentration camp for women in Europe. Her cell was in an underground prison infamously known as “The Bunker.” For three months and eight days she lived in solitary confinement next to a furnace, in total darkness, starving. Her hair and teeth fell out. She even lapsed into a mini-coma but ultimately survived the war. Many of her fellow FANYs, however, did not, including Szabó and Khan .

Odette Sansom at the FANY memorial at St. Paul’s Church in Knightsbridge, London, in 1948. She is holding Tania Szabó, daughter of SOE officer Violette Szabó.

On her second mission in France, Szabó parachuted behind German lines the day after D-Day and established contact with resistance forces in the area. On June 10, 1944, she joined Jacques Dufour in a car to Salon-la-Tour. Along the route the Germans set up a roadblock, and Dufour stopped the vehicle 50 yards away. He instructed Szabó to dash into a field as he provided covering fire. Szabó instead pulled out her Sten submachine gun and joined the fight before the pair fled into the field. She fought until she had fired all her ammunition and was captured. She joined Sansom in Ravensbrück but was executed in January 1945. Khan’s fate was equally senseless. The

Muslim princess

was a direct descendant of Tipu Sultan, an 18th-century Muslim ruler of Mysore state — today, a part of India — who pioneered rockets used as military weapons. Khan worked as a wireless radio operator in Paris. At one point she was the only SOE wireless operator in the city, operating under the code name Madeleine, and was critical in communications with the Prosper resistance network and the outside world. A Frenchwoman betrayed Khan to the Gestapo, and she and three other female SOE officers were sent to the Dachau concentration camp. There, they were executed.

All three women — Sansom, Szabó, and Khan — were awarded the George Cross, Britain’s highest civilian honor. Among the 39 FANY and SOE commandos who went into the field, 13 died as German prisoners or were killed in action. On May 7, 1948, Princess Alice, Duchess of Gloucester, unveiled a plaque at St Paul’s Church in Knightsbridge, London, dedicated to all 52 FANYs who died during World War II. In attendance was Odette Sansom. In her arms she held Tania, the only daughter of Violette Szabó, who would later accept her mother’s medal and

write a book

about her famous mother’s life. Khan became the first Indian woman in history to be honored with a memorial and a permanent

Blue Plaque

awarded by the English Heritage charity. These Blue Plaques honor notable people and organizations connected with particular buildings across London — and Khan’s can seen at 4 Taviton Street in Bloomsbury, where she lived before joining the SOE.

Replied by Maki on topic Little stories

A s members of England’s First Aid Nursing Yeomanry, or FANYs, during World War II, Odette Sansom, Violette Szabó, and Noor Inayat Khan might have worked in hospitals, driven ambulances, sent coded radio signals, fixed trucks, or even, as one FANY did during the war, taught the future Queen Elizabeth to drive. But when British Prime Minister Winston Churchill instructed the nation’s clandestine spy agency, the Special Operations Executive (SOE), to “set Europe ablaze,” the three FANYs merged their nursing roles with espionage.

The SOE, which carried out audacious sabotage plots across Europe, recruited 2,000 FANY members to the secret service. But only 39 went into the field to conduct commando operations, including Sansom, Szabó, and Khan.Each brought her unique upbringing to her missions. Sansom (pictured above) and Szabó were both born in France; Sansom to a French man killed in World War I, whereas Szabó’s father had been an English soldier. Khan was a Muslim from India descended from a sultan. But their French fluency and familiarity with military skills like marksmanship caught the eye of England’s spy masters. The commandos working for SOE in North Africa, the Far East, and particularly across Europe were the No. 1 targets of the Gestapo and the Abwehr, German military intelligence. “From now on, all men operating against German troops in so-called Commando raids in Europe or in Africa, are to be annihilated to the last man,” read Adolf Hitler’s secret Commando Order (Kommandobefehl) issued on Oct. 18, 1942. If members of the SOE were discovered, man or woman, they’d be hunted, tortured, and executed.

Noor Inayat Khan was a Muslim princess who volunteered for the British Special Operations Executive (SOE) during World War II. She became one of the first women awarded the George Cross, the United Kingdom’s highest civilian honor. It was accepted posthumously on her behalf.

After seven months of clandestine fieldwork, she was captured by the german officer Hugo Bleicher , a notorious spy catcher who personally arrested more than 100 agents and officers. Sansom was interrogated for hours at Fresnes Prison in Paris, subjected to techniques including the removal of her toenails. When she wouldn’t confess, the Nazis sent her to Ravensbrück, the most feared concentration camp for women in Europe. Her cell was in an underground prison infamously known as “The Bunker.” For three months and eight days she lived in solitary confinement next to a furnace, in total darkness, starving. Her hair and teeth fell out. She even lapsed into a mini-coma but ultimately survived the war. Many of her fellow FANYs, however, did not, including Szabó and Khan .

Odette Sansom at the FANY memorial at St. Paul’s Church in Knightsbridge, London, in 1948. She is holding Tania Szabó, daughter of SOE officer Violette Szabó.

Last edit: 4 years 10 months ago by snowman. Reason: Helped with text formatting. I know the new editor sucks :(

The following user(s) said Thank You: snowman, WANGER

Please Log in or Create an account to join the conversation.

Birthdays

- JonnySniper in 2 days

- Tomoyo00 in 3 days